Spiral lenses, a surprise ocean, Hollywood movie posters, and how blueberries became blue

Issue #2 of American Journalist

Friday, February 9, 2024

Welcome to the second issue of American Journalist. I am excited to share these papers, which have all come out just in the last two days.

1. Everything you always wanted in an optical lens but were afraid to ask

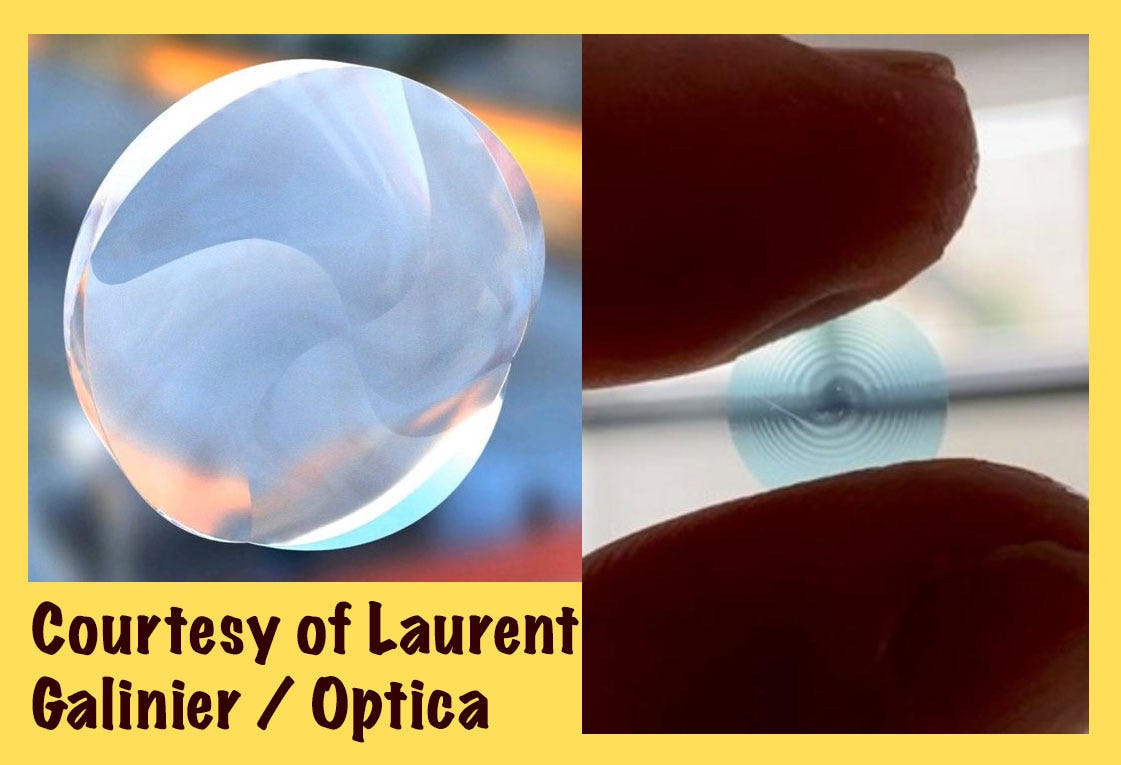

Researchers at the Université de Bordeaux in Talence, France, are announcing a new type of optical lens they call a “spiral diopter.” It looks super cool, and we think it would have brought a smile even to the curmudgeonly face of Isaac Newton, the father of modern optics.

The lens features spiralized optical vortices, which allow it to achieve multifocality—the ability to simultaneously and clearly focus light rays from distinct objects at varying distances from the lens. It works much like the progressive lenses you would find in glasses, but with less distortion. The lens design “could be crucial in miniaturizing emerging technologies while retaining their optical quality,” the researchers write. Goodbye bokeh, hello focus! Optica

DISCLOSURE: This paper appears in the flagship journal of Optica, formerly the Optical Society of America, an organization whose journals and conferences I promoted in past decades in my former role as media relations director at the American Institute of Physics.

2. Experts argue for the teaching of indigenous knowledge in science classrooms

Two researchers at Lincoln University and the University of Canterbury, both in New Zealand, published a perspective highlighting the value of Indigenous knowledge for promoting ecological resilience. They advocate bringing it into science classrooms.

“Indigenous knowledge can complement and enhance science teachings, benefitting students and society in a time of considerable global challenges,” they write. Science

3. Why are blueberries blue?

You can paint pictures with beet juice, but you can’t do that with blueberry pulp. Why? According to researchers at the University of Bristol, it’s because the color comes not from a chemical dye component of the fruit but from a “wax bloom” coating on its surface. That’s what is really responsible for their dark, Veruca-Salt-face-staining color. Bite a blueberry in half to see what I mean.

Tiny structures in the berries’ natural wax coating scatters blue light, suggesting future applications for similar coatings. The researchers say the so-called epicuticular waxes could be “sustainable and biocompatible, self-assembling, self-cleaning, and self-repairing optical biomaterials.” Science Advances

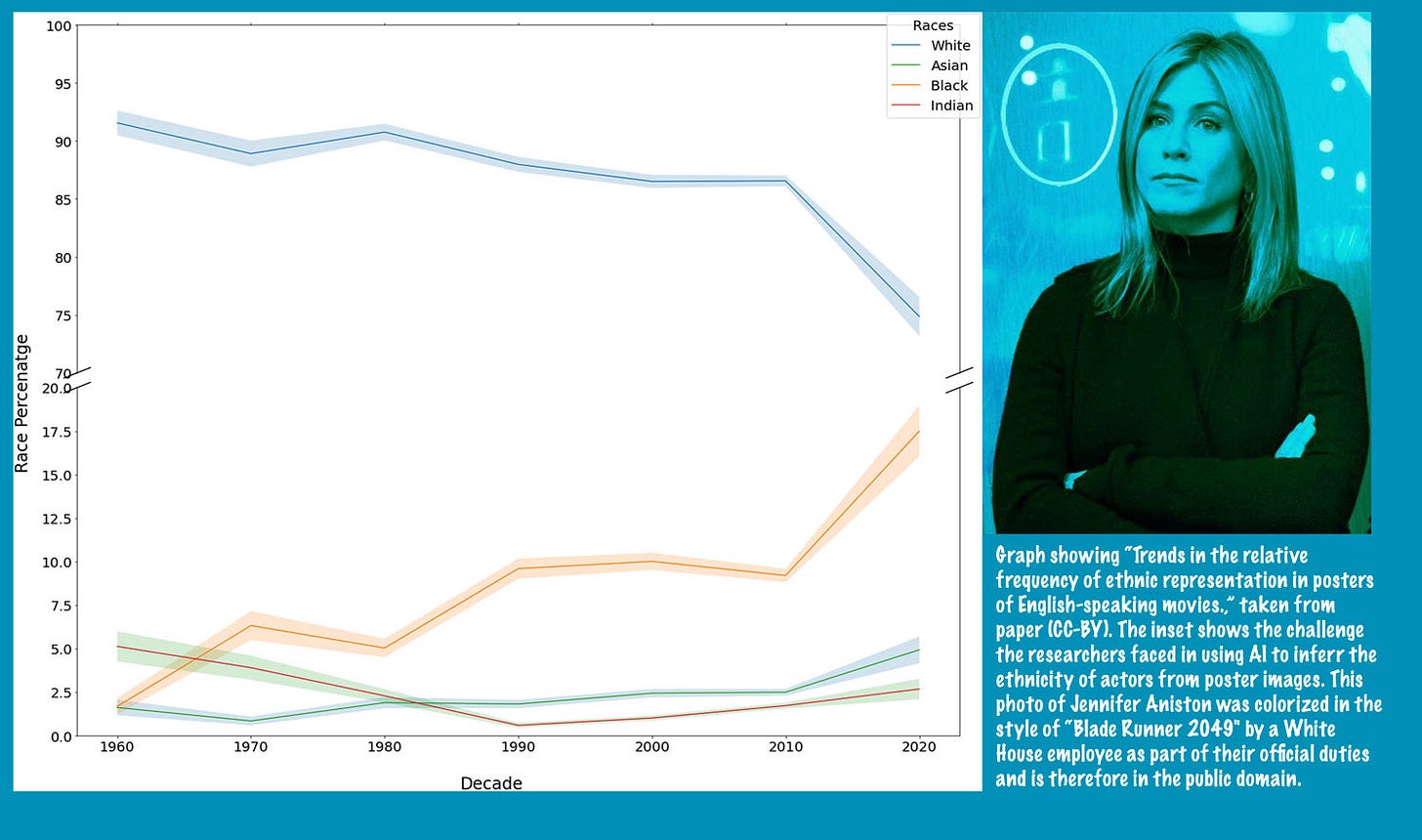

4. Bias in Hollywood? I’m shocked, shocked!

The American film industry’s Academy Awards have long been the target of what many would call justified criticism for ignoring the best work of Black artists. Sidney Poitier was the only Black man in the 20th century to win an Oscar for best actor (in 1963 for Lilies of the Field), and no Black woman had ever won the best actress Oscar before Halle Berry (in 2001 for Monster’s Ball). Perhaps the most singular slight is the fact that no Academy Award for directing has ever been awarded to a Black director. How many great movies has Spike Lee directed?!

A study this week from Ben-Gurion University in Beer-Sheva, Israel, takes a look at film industry bias through the medium of commercial movie posters. Using an AI model to analyze a database of 125,439 posters from some 35,000 movies, the researchers conclude that while bias still exists in such posters, with white actors on average depicted larger and in the center more often, the past decade has seen an increase in Asian and Black actor representation on posters. “Particularly in English-speaking movies,” they write, “the ethnic distribution of characters on posters from the last couple of years is reaching numbers that are approaching the actual ethnic composition of the U.S. population.” Humanities & Social Sciences Communication

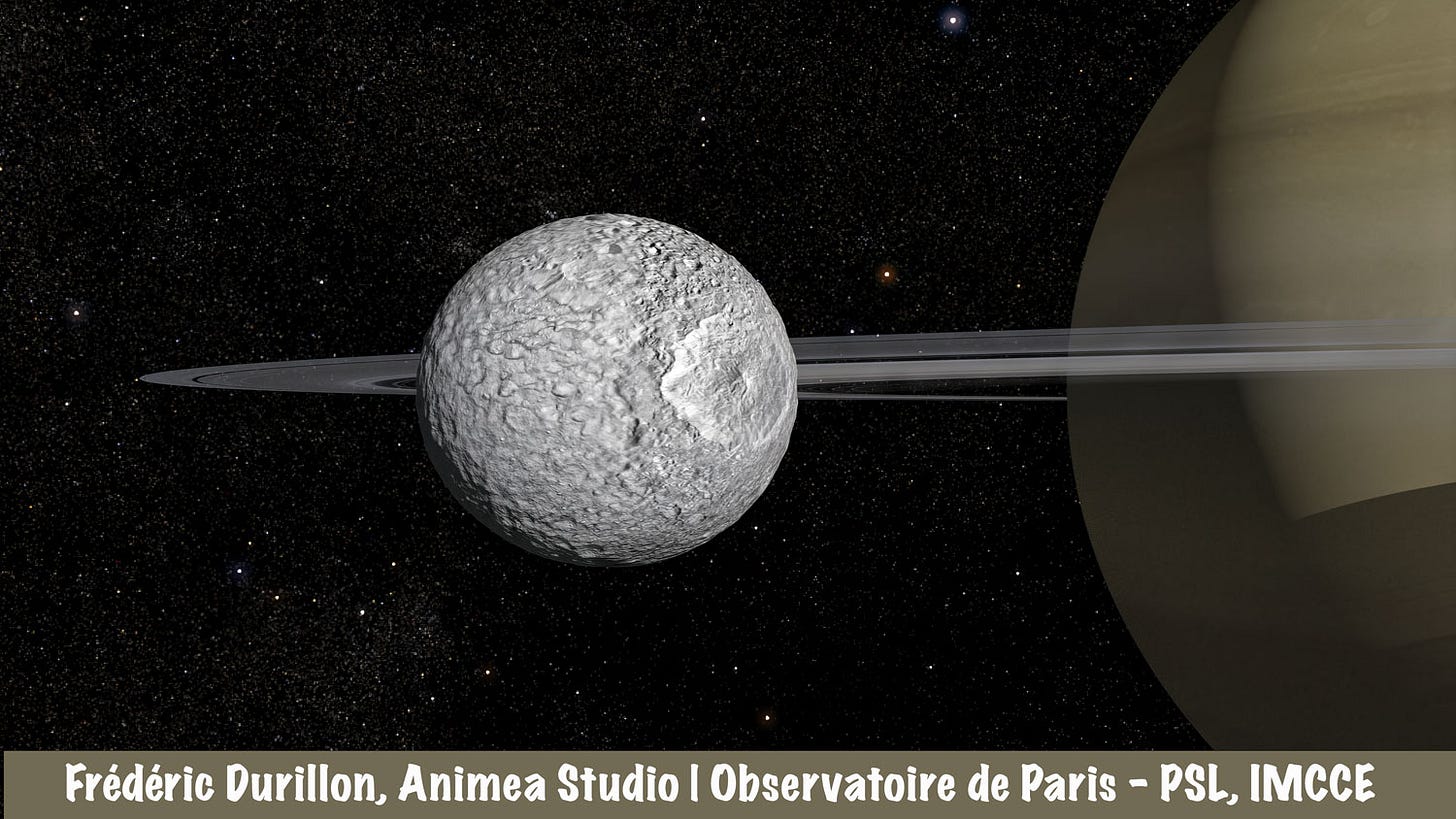

5. Guess who’s coming to Saturn?

It’s not often you will ever see the words “surprise ocean” strung together, but that’s exactly what we saw this week in the pages of the journal Nature. Researchers at the IMCCE Observatory and Sorbonne Université in Paris have discovered that Saturn’s moon Mimas, which orbits our spectacularly encircled sixth planet, has an unexpected feature: a subsurface ocean made from melted ice. This basically explodes the old theory that its interior was solid.

Mimas is named after a mythical Greek giant and has a huge crater called Herschel. The crater is 139 km (86 miles) across, and it gives the moon an appearance distinctly similar to the Death Star. Assessing data from the Cassini mission, the researchers found the surprise ocean is 20–30 km (12-18 miles) deep. By comparison, the Mariana trench, the deepest part of any ocean on Earth, only goes seven miles down. Mimas’ ocean is also young by planetary geology standards at only 25 million years old.

More papers we liked this week

• DOCENT TO THE BEAT OF A DIFFERENT DRUM. An interactive museum exhibit at the Exploratorium in San Francisco titled, “Give Heart Cells a Beat,” synchronizes stem cell–derived cardiomyocytes with the real heartbeats of visitors. Stem Cell Reports

• THE ODDS OF SURVIVAL AFTER CPR. A person’s chances of survival after a heart attack dramatically decrease the longer they wait to receive cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), according to doctors at the University of Pittsburgh. Focusing on cardiac arrests that occur in the hospital, they showed that survival declines rapidly from 22 percent after one minute to less than 1 percent after 39 minutes. BMJ

• THE SECRET OF MOUSE ERECTIONS. Researchers at the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm say a previously underappreciated cell found in the corpora cavernosa, the critical tissue for modulating penile blood flow, is central for a mammalian male’s ability to achieve and maintain an erection. Fibroblast cells in that tissue, they found, are key regulators of penile blood flow. The work was in mice, but the goal is better erectile dysfunction treatment for men. Science

Shown here is a cross-section of a mouse penis, with the fibroblast cells shown in red, vascular smooth muscle cells shown in green, and endothelial cells colored cyan. Blue is used to represent the nuclei of all the cells. Courtesy Eduardo L. Guimaraes.