Last Week’s Latest Science News

American Journalist is back because science is too wonderful, weighty, and weird to leave with the lawyers and influencers alone.

First, to explain our long absence… It was unavoidable. For the past year, American Journalist founder Jason Socrates Bardi has been working intensely on his new nonfiction potboiler The Great Math War (Basic Books, 2025), which will hit shelves by November and is already available for preorder.

More on that upcoming title soon! For now, after our long, 14-month absence from publishing, we are ready to do what we do best: sharing news and views on some of the top developments in science and medicine.

1. A Rising Tide Kelps All Sides

Turns out killer whales are not just majestic ocean predators—they’re also keen kelp stylists! Marine biologists at the Center for Whale Research at Friday Harbor in Washington State, discovered that whales in the Salish Sea will cut pieces of bull kelp with their teeth and roll it between themselves and a whale buddy—behavior they dubbed “allokelping.” Last week in the journal Current Biology, the researchers showed allokelping is not just playful bonding. (Whales like to play keep-away with objects, apparently.) This specific population of Orcinus orca ater use seaweed as a grooming tool, they claim. This is skin spa treatment on crack. Who knew even killer whales needed their salon days? Who knew skin care came in 800-X plus sizes? Move over Maybelline—Shamu’s got this one.

Using drones for several months in 2024, the researchers observed resident killer whales in the cold Pacific waters of the Salish Sea surrounding islands off the coasts of Washington and Canada, repeatedly cutting pieces of bull kelp as a tool to roll across their bodies in a coordinated way. They hypothesize the behavior is a form of “social skin maintenance,” and they even recorded whales fetching kelp accidentally dropped and replacing it in between them then repeating the rubs. How long before Gweneth Paltrow’s GOOP offers an Orca kelp facial, we wonder?

2. Ink Jet Islets for Type 1 Diabetes

Islet transplantation can transform life for people with type 1 diabetes, restoring their body’s ability to produce insulin, dramatically improving their blood sugar control without the need for insulin, and basically curing their disease. But because it relies on the very limited number of pancreas transplants available from deceased donors, only a few hundred people each year get the surgery—compared to the more than one million people in the United States who live with type 1 diabetes. For years scientists have sought ways to increase the availability of islet transplantation by finding sources from transgenic pigs or by growing them in the laboratory.

Now researchers claim to have successfully 3D printed functional human islets, the clusters of cells in the pancreas that produce insulin. Using a special bioink and human pancreatic tissue, they successfully made islets that stayed alive in the laboratory and produced strong insulin responses to glucose for up to three weeks. The printed islets were designed to be implanted under the skin in a minimally invasive procedure (as opposed to the traditional procedure, where they are transplanted into the portal vein of the liver). There is no paper yet—this was work they presented at the European Society for Organ Transplantation 2025 congress in London. The work shows promise, and we hope it leads to safer and more effective type 1 diabetes treatments.

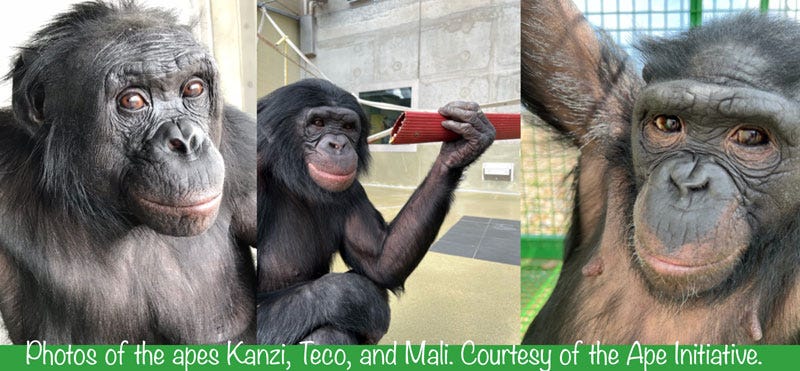

3. They Are Not Laughing With You

Laughter is not just some involuntary sound you make when a silly clown trips over his licorice shoelace and pratfalls on his bum. Nor is it without power. Even forced or fake laughter on laugh-track TV comedy can bring a smile to your face. Laughter is primitive. It’s universal. It’s raw. It’s divine. It’s a deep-rooted evolutionary trait, and, no—it’s not solely human. As a study in the journal Scientific Reports from UCLA and Indiana University reminded us last week, monkeys laugh as well.

Bonobos, our cool, hippie cousins in the ape family, are also riotous in chortle. They affect each other with their laughter and they are, in turn, affected by it. In the study, anthropologists trained four bonobos to expect a fat, fruity grape inside a black box and a great big zilch inside a white box. The apes learned to tear into the former and ignore the latter. But what’s one to do with a grey box? Turns out, when bonobos hear kind kin laughter as they contemplate that very question, they are three times more likely to open the gray box. The laughter put them in the mood to expect a reward. Gimme ’nobo a ’nother grape, Daddy! Or as the scientists put it: Positive affects lead apes to expect positive future outcomes. Who’s laughing now?

4. The Dog Days of Wrist Pain

The wonderful world of dog walking is surprisingly dangerous, as was on full display last week in the journal Science Advances. A study there revealed that yanks and jerks by our furry best friends lead to a shocking number of leash-pull injuries to the finger, hand, and wrist. Researchers at Raigmore Hospital in Inverness, Scotland, and Sengkang General Hospital in Singapore looked at almost half a million such incidents described in five studies published between 2012–2024. They found that almost three-quarters of the injured dogwalkers were female and nearly a third were elderly, and they estimate that wrist fractures alone cost more than £23 million annually.

Why does this matter? Because it’s addressable. A few simple interventions might be able to significantly reduce such injuries. Many women and elderly people who suffer osteoporosis may be at higher risk and could be educated and warned. New leashes could implement safer twist-and-wrench, breakaway failsafe technology to avoid their becoming medieval torture devices. Focused dog training could address this problem as well. Squirrel chasing baaaaad!

5. I Want Canoe. You Can’t Handle Canoe.

Commitment to excellence for some scientists means showing up early or staying late. Perhaps sacrificing holidays to get that grant finished. Or it could mean suffering time away from a family vacation to go to a dreary congress and present a paper to glassy-eyed colleagues and shell-shocked grad students. But imagine this: strutting around in a rough-hewn tunic and fashioning your own axe out of rock, stick, and leather. Big-man chopping down giant tree! Then imagine putting your life on the line to paddle across a treacherous 140 miles of open ocean with nothing but the sun, stars, and your instincts to guide you. That’s not commitment—it’s craziness. And it’s exactly what Yousuke Kaifu and colleagues from the University of Tokyo did in an experiment to test a theory they call the “dugout canoe hypothesis.”

Using hand-made replica 30,000-year-old stone tools, they built a 24-foot canoe canoe from a single Japanese cedar tree and set out to recreate a treacherous sea crossing from Taiwan to Okinawa to prove it could have been done by ancient, unknown Paleolithic ancestors. The 45-hour crossing took them across the Kuroshio, one of the world’s strongest ocean currents. But with heroic, test-of-endurance-type team paddling and an understanding of the wind and the drink, they made it, recreating a journey first canoed by the brave and the desperate, who crossed the ocean to settle on remote islands dozens of millennia ago.

6. International House of Handshakes

Okay, so then there was this last week: A team of psychologists and sociologists at the University of Silesia in Katowice, Poland, explored how cultural norms affect expressions of romantic affection. How are handholding, intimate hugs, and smoochy kisses linked to a person’s sense of satisfaction in their own romantic relationship?

There are major cultural differences around the world when it comes to both public displays of affection and people’s attitudes toward it. In some places it’s completely frowned upon, even illegal. In others, it’s embraced, accepted, and even celebrated. Awww! In order to gauge cultural differences, the Polish researchers surveyed 62 men and 108 women in Indonesia, 56 men and 64 women in Nepal, and 72 men and 99 women in Poland. All were age 18–49 and were heterosexual. The researchers asked them how much private affection they experienced in their own romances, how satisfied they were in those relationships, and what their attitudes toward public displays of affection by other people were.

Poland had the most public displays of affection, and people there had the least negative attitude toward it, with one narrow exception. As previous studies in Poland have found, people who are not romantically involved or unhappy in their relationships are more likely to have negative attitudes towards other people displaying affection. Lonely are the dumped, the spurned, the lovelorn, and the just plain unlucky-in-love. And angry are they as well, apparently. We always hate what we cannot have.

The new study found more or less the same pattern in Nepal, even though culturally that country sees much less public displays of affection than Poland. But the study found something else as well. The results in Indonesia showed the inverse: when people were more satisfied with their romantic relationships, they were actually also more likely to express negative attitudes when seeing people engaged in public displays of affection. What’s good for me is bad for you on that Southeast Asian archipelago.

Somehow the Nepalese reported the highest level of satisfaction in their relationships, followed by the Polish participants. The Indonesian participants reported the lowest. So what’s the big takeaway? Obviously if you want to be happy, show some love and be loved in return. The importance of affectionate behaviors in romantic relationships is universal, even if you have to account for cultural sensitivities when expressing them.

7. Translational Potential of Exercise

When people say anti-aging, the word they really mean to say is geroprotection. It’s an unwieldy term for a well-fated science that has blockbuster potential. And why not? One basic human desire is to live. Many of us, most of us, want to live longer—and stay vibrant, sharp, and full of good energy as we do. Oh sure! Diet and exercise, exercise and diet. We all know the best way to stay alive is to stay alive the best way, and people who are into that sort of thing will tell you it’s all about resilience: reducing inflammation, boosting metabolism, keeping your body in tip-top shape to delay the onset of disease and help you live longer. Sensible, regular exercise is the sugar daddy of resilience.

How do we know this? A new study from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Xuanwu Hospital Capital Medical University in Beijing goes a long way toward answering that question. Published last week in Cell, they compared the physiological effect at the molecular level of short-term versus long-term exercise in 13 healthy adult men. Repeated long-term exercise triggered adaptive changes. No surprise there. But they found some of these changes reduced senescence, which we have written about before, and lowered inflammation. They identified a mechanism involving the metabolism of a human molecule known as betaine, a naturally occurring amino acid derivative found in dairy, meat, and plants. It appears to mimic the effects of exercise, which suggests betaine, some derivative of it, or some upstream or downstream effector could be a future target for healthy aging drugs.

8. MAGA + MAHA = Mitochondria. Good? Maybe Not.

According to Hannah Seo’s thoughtful feature in The Atlantic last month, the Make America Healthy Again movement sees the humble mitochondria as the hobgoblin of chronic disease. Robert F. Kennedy Jr. discussed it on Joe Rogan’s show in 2023, long before he became secretary of Health & Human Services. And the ill effect of chronic stress and ultra processed foods on these organelles inside human cells is mentioned in the new White House MAHA report. And U.S. surgeon general nominee Casey Means apparently wrote an entire book on the subject. But will the simple-minded mitochondria = good approach lead to widespread improvements in human health? It remains to be seen.

Mitochondria are good, there can be no doubt. For something so ancient as to persist across all species we see in our modern world, it’s gotta have something going for it, right? Indeed, it does. The mighty mitochondria is like the Tesla supercharging station of the cell, producing a molecule known as ATP. But can you have too much of a good thing?

We pondered that this week after researchers from the University of South Alabama and the University of Texas Health Science Center investigated the role of nerve cell–cancer cell interactions in breast cancer metastasis. In the journal Nature, they describe how they labeled mitochondria and demonstrated how neurons that innervate cancer cells can transfer mitochondria into them, enhancing the cancer cells’ metabolism, plasticity, and resilience—in other words, the exact opposite of what you want. They showed that breast cancer cells proliferating at distant metastatic sites, particularly in the brain, are selectively enriched with neuronal mitochondria.

This is basic research, don’t get me wrong, but it demonstrates mitochondria may play a key role in cancer metastasis, making the MAHA + mitochondria story more complicated than it seems.