Fish stripes, butterfly flaps, California wildfires, the virus formerly known as monkeypox, and why they want to dehydrate the stratosphere

Issue #8 of American Journalist

Friday, March 1, 2024

We are ending this very interesting last month in science with a few critter-creature stories as well as a big safety question about a new geoengineering approach to mitigating the effects of climate change—JSB

1) Dehydrate this!

Our first reaction this week upon reading the headline of a press release about a new study examining the “feasibility of dehydrating the stratosphere” was: OMG, they want to dehydrate the stratosphere?! Nice idea, but let’s see what legitimate experts in the top government agencies studying climate change have to say about this. And then we read the paper and realized: These are those experts!

Scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in Boulder, Colorado, and NASA Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California, have done a deep dive into the feasibility as well as the pros and cons of an “intentional stratosphere dehydration” strategy for fixing climate change.

(As an aside, they innocuously label this strategy “ISD,” but we reject that designation. It’s a classic example of hiding behind an abbreviation—choosing acronym over acrimony. There is potential controversy here that needs to be aired. Things we do in the upper atmosphere should see the light of day! There’s less cloud cover the higher you go, so let’s not be so opaque on the ground.)

So what is this strategy? The approach is based on the idea that reducing water in the stratosphere would help reduce “radiative forcing of the Earth.” In simple terms, the water in the upper atmosphere contributes to the greenhouse gas effect by absorbing outbound heat in the form of longwave radiation emitted in the atmosphere or reflected off Earth’s surface, as diagrammed here. Removing water in the stratosphere through “intentional dehydration” would increase the outbound heat. Simple, right?

Maybe. Changing the world to change the world may not be the worst idea ever—but it may not be the best one either. We’ve tried it before. The eugenics movement was based entirely on the notion that selective breeding of “superior” humans and forced sterilization or outright murder of the less-than-superior would improve humankind. And here’s another example from a century ago: In World War I, people marched headlong into the trenches thinking that war was necessary to end all wars (to quote the famous line by H.G. Wells). Get in, git ’er done, yadda-yadda-yadda, and we’ll enjoy world peace, global trade, and prosperity on the Paris and London streets.

We are not saying geoengineering is as criminally suspect as eugenics or as quagmiringly dangerous as WWI. We would never completely dismiss innovative engineering approaches to climate change mitigation because—after all—they are addressing climate change. This is a defining challenge of 21st century science, and we’d love to see solutions. But we love safety first and so would like to know what safety measures would be put in place. Science Advances

EDITOR’S NOTE: American Journalist editor Socrates Bardi started his career in the Earth science directorate at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center 25 years ago, writing about climate change, atmospheric science, and weather modeling.

2) Monkeypox revisited

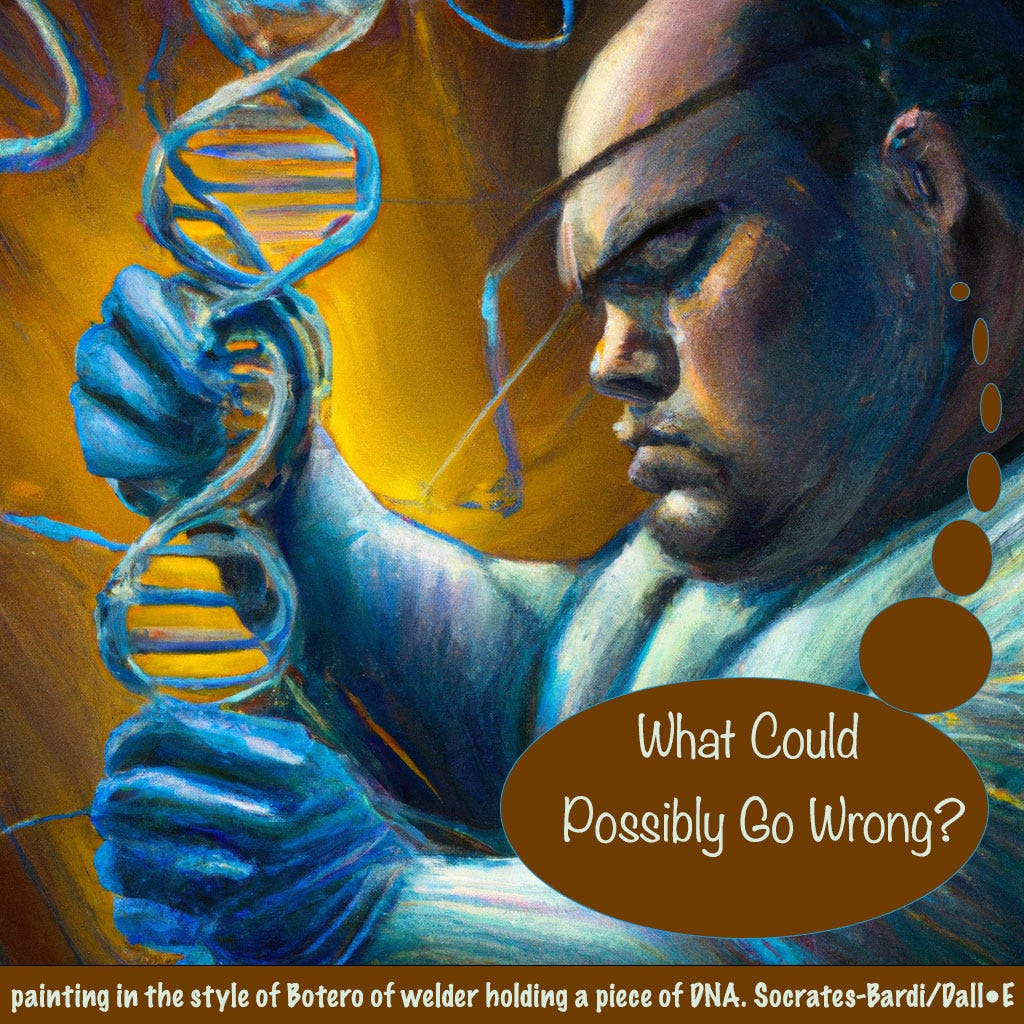

This summer marks two years since the World Health Organization declared mpox, the virus formerly known as monkeypox a “public health emergency of international concern.” It’s a designation they have used only a handful of times since it came into existence after the SARS outbreaks in 2003.

In an analysis of the monkeypox episode, epidemiologists at the University of Washington in Seattle report that this latest public health emergency of international concern was driven by undetected dispersal and local transmission in the form of community spread that took place prior to detection. They also found travel bans would have had only a minor impact on the outbreak. “Our findings highlight the importance of broader routine specimen screening surveillance for emerging infectious diseases,” they write. Cell

NOTE: We realize that the official name for monkeypox has now been changed to mpox, and we don’t oppose that change. But it feels a bit like X so far. Most media outlets will go through the tedium of saying every time “formerly known as Twitter,” but we have yet to see anyone calling it just “X.”

3) Antidepressant use and California wildfires

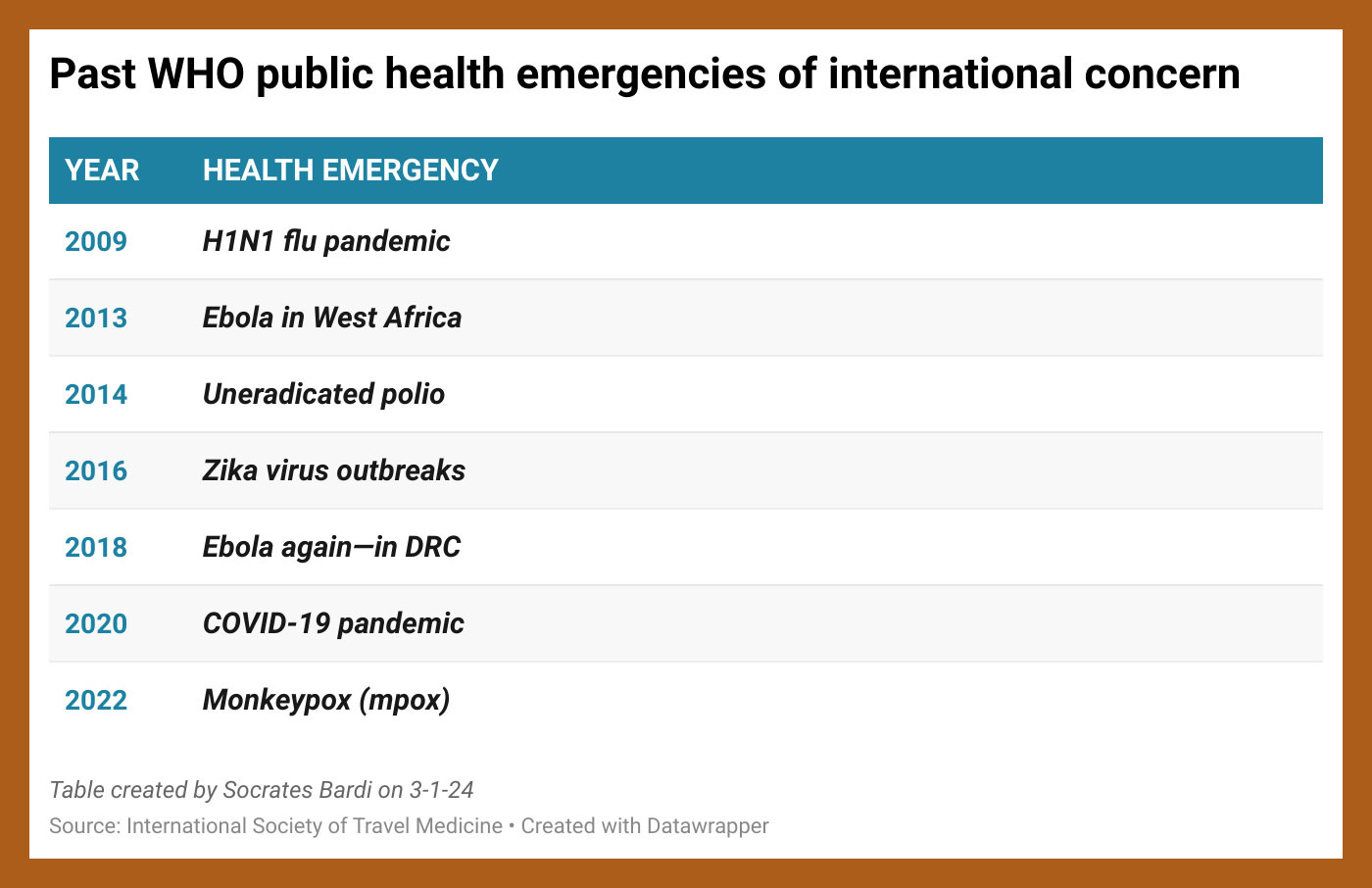

Looking at the prescription filling habits of seven million people living in California in places directly impacted by 25 large wildfires from 2011–2018, researchers at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta found a significant increase in antidepressant, anxiolytic, and mood-stabilizing drug prescriptions during fire periods compared to before. That may not be surprising, but it’s nevertheless useful.

“This study’s results suggest that large wildfires may exacerbate certain mental health conditions,” say researchers, “necessitating a comprehensive public health approach that ensures access to a wide variety of services, including those that improve mental health resilience before, during, and after disasters.” JAMA Network Open

4) Flapping to the beat of a different bug

Some species of butterflies have evolved colors and patterning that allow them to impersonate other, less tasty species of butterfly and avoid becoming a tragic snack. Apparently that’s not enough. The pretenders also mimic those other species in the way they flap their wings, according to researchers at the University of York in England.

Analyzing high-speed video of 351 individual butterflies from 38 different species, they observed pervasive flight mimicry across very different evolutionary timescales. In some butterflies it evolved in an offshoot species that only “recently” (less than 500,000 years ago) separated from the species it mimics. They also saw mimicry between species that split more than 70 million years ago. PNAS

5) Fish eat fish—and sometimes they change color before they do

An interesting evolutionary strategy employed by the striped marlin Kajikia audax is described this week by researchers at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin in Germany. Marlin are large predatory billfish famous for their impressive, protruding rostral, those sword-like upper jawbones that make for masterful trophies and middling team mascots (Go St. Louis Cardinals!).

Marlin are known for speed as well as spikes. Some of the strongest swimmers in the ocean, they’re capable of explosively fast strikes—the better to skewer their prey. But therein lies the challenge: How do species of marlin that hunt in groups avoid stabbing each other as they swim around constantly striking at high speed?

Analyzing high-resolution drone footage of groups of marlin attacking schools of Pacific sardines (Sardinops sagax), the researchers observed individual marlin undergoing rapid color changes as they hunted. They intensified the contrast of their body stripes immediately before striking and decreased the intensity after an attack. The researchers hypothesize that the color change signals their motivation to attack, warning the others. Current Biology