Ebola drugs, COVID vaccines, lab leak (again), transgender rights, and the enigma of the direct-to-consumer microbiome test

Issue #10 of American Journalist

Friday, March 15, 2024

Cave Idibus Martiis (“beware the Ides of March”). Shakespeare said it. But did they celebrate Pi day the day before and stuff themselves on sugary pastries back in Elizabethan England—or for that matter in Roman times?

1) Direct-to-consumer microbiome tests—A call to strengthen their regulation

A blistering perspective this week by experts at the University of Maryland highlights the oddly regulated and questionably effective marketplace of direct-to-consumer microbiome tests. The FDA does not regulate these tests—that responsibility falls to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS)—and apparently CMS doesn’t require companies selling microbiome test kits styled for personalized medicine to provide any evidence they can accurately identify gut microorganisms and their relative abundance in consumer samples.

We would call the temperature of this essay scalding. Even though it doesn’t name names, it reveals bluntly how our basic knowledge of microbial diversity in the human gut is sorely lacking. We currently don’t even know how to define a healthy human microbiome on the broad population level—let alone for individuals. Worse, many tests currently sold to consumers “lack analytical validity.” That’s huge. Test results from a single sample have been shown to be inconsistent across different laboratories and even within the same laboratory, according to the editorial. Micobiome test companies often hawk their wares as services, offering periodic tests rather than one-offs and promising to use that data to steer personalized monthly supplements subscriptions, bespoke dietary guidelines, or other upsells.

Look, people, please don’t misunderstand. We love the idea of direct-to-consumer testing and at-home microbiome testing in particular. And we have no doubt that as this century proceeds and our knowledge expands, the science of analyzing good and bad bugs in our GI tract will mature, increasingly come to reveal our state of health, and inform interventions for all sorts of human diseases. But the vague promise of manipulating the microbiome now, so unregulated and before we even know how it works, makes the promise of these companies seem more like that of a doomsday cult than a wellness firm. “Pray with us because the world is ending,” cults like to say as they ask for cash and faith. “And if the world doesn’t end, it’s because the payers— Sorry! Prayers—were answered.” Science

2) COVID-19 Lab leak hypothesis, revisited

A new paper from the University of South Wales in Sydney, Australia, is sure to reignite a controversy over the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic. Unless you have been sleeping under a rock for the last four years, you will know that the two leading theories as to the emergence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus are that of lab-leak versus zoonotic infection—the competing ideas that it jumped to humans after a research accident or naturally, from a bat or some intermediary species as many other emerging infections do (and as similar coronaviruses SARS and MERS previously did).

What would proof of a natural, out-of-the-wild zoonotic origin look like? Smoking gun evidence would be positive PCR swabs showing an unbroken chain of transmission from bats (the natural hosts of coronaviruses) to some intermediary mammal, fish, or bird species to the Wuhan wet market to the first human cases. That evidence has not materialized and probably never will.

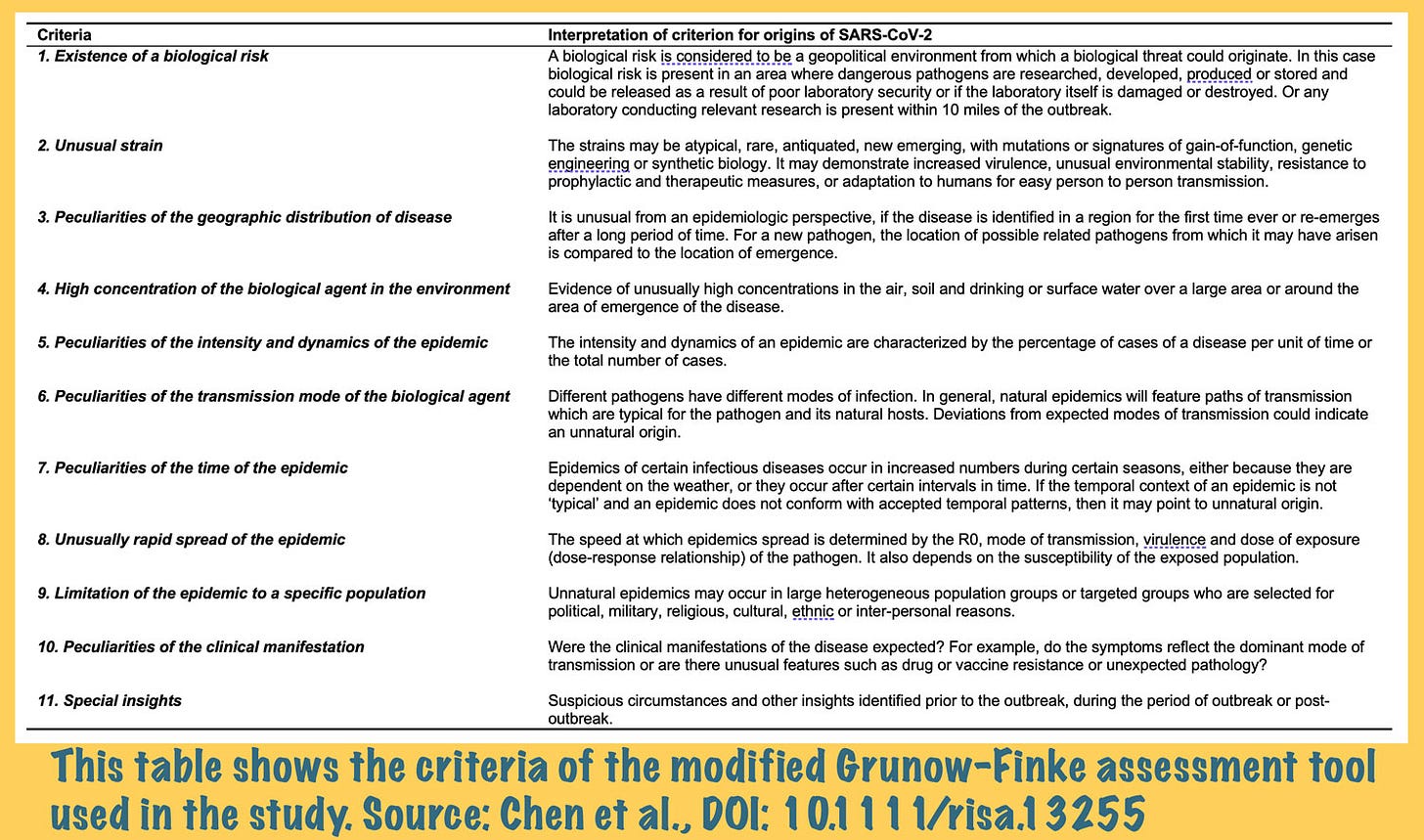

What would lab leak proof look like? Direct proof could come in lots of forms, though this study does not provide any. Instead, the Australian team used something called a modified Grunow-Finke assessment tool to look at the origin of SARS-COV-2. This tool scores the likelihood of natural or unnatural origin based on 11 criteria, shown in the table below.

The researchers report the tool returned a score of 41/60 points (68 percent) likelihood of an unnatural (read: lab-leak) origin for SARS-CoV-2. “This risk assessment cannot prove the origin of SARS-CoV-2,” the researchers write, “but shows that the possibility of a laboratory origin cannot be easily dismissed.” Whether or not they are right about the lab leak, they are definitely right on that last score. Nothing with this pandemic has been easy. Risk Assessment

3) The last mile for coronavirus vaccines

When COVID-19 vaccines were first introduced into the Sierra Leone in West Africa, centralized distribution schemes often required people who lived in rural communities make long commutes to health centers to be vaccinated—trips that could cost them more than a week’s worth of wages. Such access issues are one of the reasons why as recently as November, only 33 percent of people in Africa had received even their first dose of a COVID-19 vaccine (by comparison most Americans had anti-vaxxed their way out of at least 2-3 shots by then).

How effective would last-mile delivery programs bringing vaccine to those people in their own communities have been? In partnership with the Sierra Leone Ministry of Health and Sanitation and the international nonprofit Concern Worldwide, researchers at the University of Oxford and Yale University asked just that. They conducted a randomized controlled trial in 150 communities representing some of the most remote, inaccessible areas of Sierra Leone and showed community mobilization of vaccine and health professionals almost immediately increased immunization rates by about 26 percent in those communities. The cost for organizing, transporting, and administering the vaccine doses was $1,560 per village or about $33 per person. The vaccine itself was provided by the COVAX program for free. Nature

4) Ebola shows its vulnerable side

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and the recent monkeypox outbreak (m-pox if you must), one of the last major disease outbreaks to be declared a World Health Organization “public health emergency of international concern” was Ebola—twice, in fact, in the last decade: in West Africa in 2014 and in Democratic Republic of the Congo in 2018.

Ebola is caused by a nasty zoonotic virus that’s not adapted well for human hosts. Because of that infections are very often deadly, with case-fatality rates exceeding 50 percent—and in some outbreaks as high as 90 percent. There is a vaccine and also two FDA-approved monoclonal antibody treatments for Ebola, but there’s also a huge need for effective, less expensive, and easier to administer antiviral drugs for on-the-ground responses to outbreaks. (Monoclonals are typically injection-only.)

Now researchers at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston have demonstrated the potential of an oral antiviral drug called obeldesivir for saving lives in future outbreaks. In animal studies, they showed that a once-daily regimen of the drug beginning 24 hours post-exposure was effective at protecting cynomolgus macaques against the worst outcomes of infections with Sudan virus, which is another type of Ebola-adjacent filovirus. The drug conferred 100% protection against lethal infection, in fact. “Our results offer promise for the further development of [obeldesivir] to control outbreaks of filovirus disease more rapidly,” the researchers contend. Science

5) Transgender rights at the university

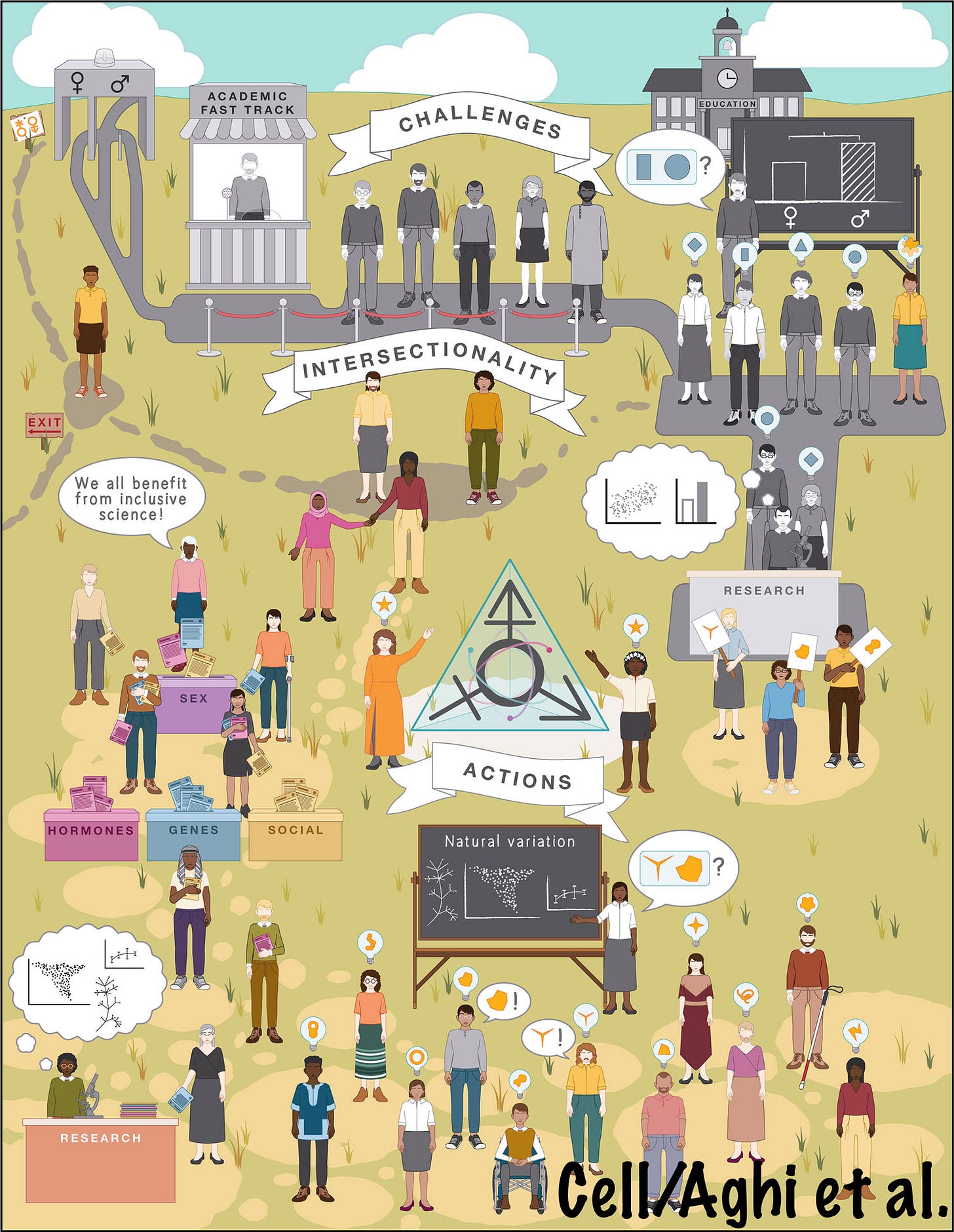

The systemic barriers people belonging to sex and gender minorities face in academia were thrust front and center this week in a commentary from experts at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, Michigan State University in East Lansing, and the Center for Applied Transgender Studies in Chicago. The article summarizes the contemporary oppression of transgender people and suggests actions that could help build a more inclusive academy.

“While intersectional movements such as Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries, anticolonial movements in the South Asian subcontinent, and third-wave feminists made significant headway toward trans liberation, the trans community still faces considerable systemic oppression in the academy and in society,” say the researchers. “Anti-trans activists continue to use pseudoscientific claims to justify discrimination, oppression, and elimination of people outside of essentialized ‘biological’ categories.” Cell

Who should be allowed access to microbiome technology then? You can disagree with the claims made by these companies, but they are all heavily footnoted with “peer reviewed research” and “PhD scientific advisors”. So who should decide what I can buy? Note that CLIA certification is one way to validate basic quality control. If you start demanding efficacy before a lab test can be sold, doctors will lose a lot of tools.