AI, happiness, anger, racism, e-cigarettes, moths v. bats, and forever chemicals

Issue #1 of the American Journalist

Wednesday, February 7, 2024

Welcome to the inaugural issue of American Journalist. We hope you enjoy reading about this research as much as we did.

1. The high cost of chemicals in the American diet

This week saw a double-whammy drop of worrisome studies from opposite ends of the United States concerning so-called “forever chemical”—pollutants known as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). These chemicals are synthetic organic compounds and named for the fact that they have multiple fluorine atoms attached to an -alkyl chain of carbons and hydrogens. But don’t let the fancy name fool you. These chemicals are hormone disruptors with known human health risks. Found in cosmetics, food containers, fabrics, furniture, packaging, and other commercial products, they don’t readily break down in the environment. And they can seep into groundwater from “soil hotspots,” including 30 new ones identified just this week and slated for cleanup by the U.S. Military.

Now a paper from the University of Southern California in Los Angeles described a longitudinal study of 123 young, primarily Hispanic adults enrolled in the Southern California Children’s Health Study (CHS) and another 604 young adults who participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination survey (NHANES). This was the first study to look at the association of PFAS and diet. Described in the journal Environment International, the study compared blood samples to self-reported surveys of eating habits. It found higher PFAS levels in people who consumed more tea, pork, hot dogs, and processed meats. Eating more home-cooked meals, on the other hand, was associated with lower PFAS chemicals in the blood.

A second study from New York University focuses on the cost of prenatal exposure to another class of hormone-disrupting chemicals called phthalates, which are known as “plasticizers” and are often added to vinyl flooring, lubricant oil, soaps, shampoos, hair sprays, and other products. The NYU researchers linked plasticizer chemicals to some 56,600 U.S. preterm births in 2018—accounting for 10 percent of all preterm births that occurred in the United States that year. The associated medical costs, they estimate, will be $1.6–$8.1 billion over the lifetime of those children. Lancet Planetary Health

2. Could urban planning make you less racist?

We love studies that suggest interventions for health or social problems, even if those solutions appear complicated and expensive, like fundamentally reimagining the modern city. That would seem a tall order, as tall as a giant tree, and perhaps you find us saps for buying it. But if hope for the future were a sticky substance, it would be absolutely seeping from this fascinating paper out of the Santa Fe Institute in New Mexico, which looks at structural reasons for racism. Segregation of neighborhoods along racial lines and the historic maintenance of those invisible barriers through practices like “redlining” have contributed to racism and bias and have driven racial disparities in health outcomes, education, employment opportunities, and income.

Standing in stark contrast to the segregated neighborhoods of old are the potential more cosmopolitan public spaces of the present and future, “where a diverse range of people can experience positive interactions with one another,” the researchers said in a statement to the press. Their new paper in Nature Communications finds evidence of lower implicit racial biases in larger, more diverse, and less segregated U.S. cities. (Paper not available as of press time.)

NOTE: We have no idea what the image above has to do with this study, but it was provided by the researchers, and we love it! The 2018 acrylic on canvas painting is part of an art installation on display at the Santa Fe Institute, so maybe its relevance to the research is by proximity alone. The painting “Ambiguity in All Directions,” is © Jan Gerrit Schuurman. Used with permission.

3. OPINION: Close the data sex gap in sports medicine

Despite years—generations now—of growing female participation in sports at every level, a yawning data sex gap has emerged in sports medicine. A 2021 survey showed how wide this gap truly is. Looking at 5,261 studies published in six top physiology and sports medicine journals from 2014–2020 found that women only represented a third of the 12.5 million people who participated in the separate studies. And only 6 percent of the studies were focused exclusively on women, compared to 31 percent devoted just to men.

This gap is especially apparent for women who are in midlife or older, according to an editorial this week by Kelly McNulty of the U.K.’s Northumbria University in Newcastle upon Tyne and colleagues. They are issuing a call to action this week for the sports medicine community and its funders to close this gap and study such things as the impacts of perimenopause and postmenopause on exercise and physical activity, how diet and exercise can impact health and wellness for women at midlife, and how treatments like hormone replacement therapy impact training and performance. British Journal of Sports Medicine

4. Could AI predict if an antidepressant will work?

One of the awful barriers to effectively treating clinical depression is the “cold open,” that uncertain time it takes for common depression drugs to kick in—often weeks—and the fact that many people and their doctors only find failure in that time they and must transition to another drug. Now a new study of 229 people undergoing treatment for depression finds that AI trained on MRI head scans as well as clinical data could predict much sooner (within a week) whether a drug is going to work.

Called the Establishing Moderators and Biosignatures of Antidepressant Response in Clinical Care (EMBARC) study, this was a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial that took place at Amsterdam University Medical Center and Radboud University Medical Center in the Dutch city of Nijmegen. It looked at an AI’s ability to predict the effectiveness of taking the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) sertraline, better known by the brand name Zoloft, and the study authors say it shows treatment responses can be predicted earlier. That’ll be a boon to many people if larger clinical trials prove it works. “A lean and effective protocol,” they write, “could individualize sertraline treatment planning to improve psychiatric care.” American Journal of Psychiatry

5. An atlas of the female reproductive tract

Based on studies in mice, a new paper from the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) and Heidelberg University in Germany details the physiology of the female reproductive tract, sheds light on the poorly understood process of aging in the ovaries and other tissues, and shows how this tract undergoes extensive remodeling during reproductive cycling. “Our atlas provides extensive detail into how estrus, pregnancy, and aging shape the organs of the female reproductive tract,” the researchers write, “and reveals the unexpected cost of the recurrent remodeling required for reproduction.” Cell

6. A shorter test for anger

We all feel anger, and this emotion is largely maligned in modern society and often deemed completely inappropriate in schools and the workplace. We don’t argue with that at all, except to caveat one bit by saying that anger fills a natural spot on the spectrum of human emotions. Some dignified and non-violent forms of anger would seem OK, even appropriate, in any setting. We are talking about anti-racist anger, anti-sexist anger, anti-corruption anger, and all the anger one feels when recognizing social injustice and human suffering. We are talking about righteous anger—the anger of motivation to justice, which has fueled every protest and reform movement in human history (and is completely compatible with all peaceful protest).

But not all anger is the same. Anger also fuels awful violence. Now we are talking about clinically and socially pathological “problematic” anger. It drives untold human suffering. And turned inward, problematic anger can contribute substantially to poor mental health. Some people wrap themselves in an iron-shirt of anger when they have underlying mental health problems. Interestingly, anger is not just an armored mask. It can also be used to predict things like depression and PTSD.

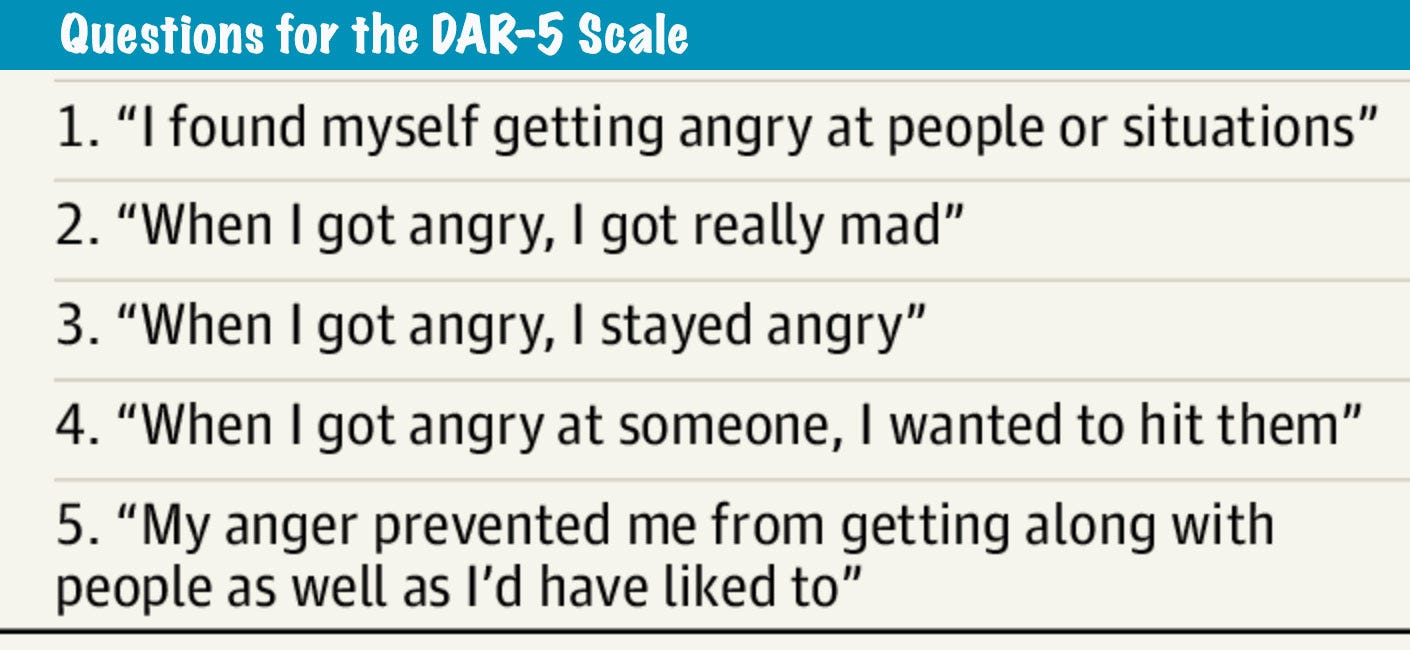

No surprise that militaries are interested in assessing anger as a way to predict and prevent those mental health issues. According to a paper this week from the Phoenix Australia–Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health at the University of Melbourne, the standard measure of anger is an empirical test called the Speilberger State Trait Anger Expression Inventory, but it has limitations. The shorter, 5-item Dimensions of Anger Reactions scale (DAR-5) was developed to assess anger more easily, based on asking how people respond to five statements. Now there is an even shorter DAR-3 scale, which makes problematic anger assessments based on only three questions. This week’s study of 71,010 active and former military personnel in the United States and Australia showed that the briefer test was valid, effective, and “offered a reliable and valid approach to measuring problematic anger.” JAMA Network Open

7. With crashing tymbals, this moth lives to fly again

Yponomeuta moths have a strange ability to buckle structures known as tymbals with their wings and produce clicking sounds audible to bats that serve as an ultrasound protective mechanism against this predator, according to a study from researchers at the University of Bristol in England. This is but one example of the extensive acoustical weaponry in the moth-versus-bat survival dance. Others include acoustic stealth camouflage, moth decoy echoes, and moth sounds that jam bat echolocation. PNAS

8. More papers we like this week

• A REMARKABLE CONVERGENT EVOLUTION. From the tiny, painful prick of a bee to the gigantic tooth-like tusk of the narwhal whale, a common solution nature has found over and over for the problem of how to prick a predator or prey is the ubiquitous sting. Amazingly, according to researchers at Nanjing University in China and the University of California, San Diego, even though they emerged separately over the course of evolution and vary widely in scale and material, the shape of all stingers can be described mathematically according to a common power law. PNAS

• MUSIC AS MEDICINE. McGill University doctors published results from the 2021–2022 Music for Subanesthetic Infusions of Ketamine (MUSIK) randomized clinical trial for improving the response of ketamine infusions for treatment-resistant depression. JAMA Network Open

• COULD AI CHATBOTS IMPROVE MENTAL HEALTH? Researchers at the London-based AI and health care company Limbic used natural language processing to analyze feedback from 42,332 people and showed that chatbots could increase referrals, providing “strong evidence that digital tools may help overcome the pervasive inequality in mental healthcare.” Nature Medicine

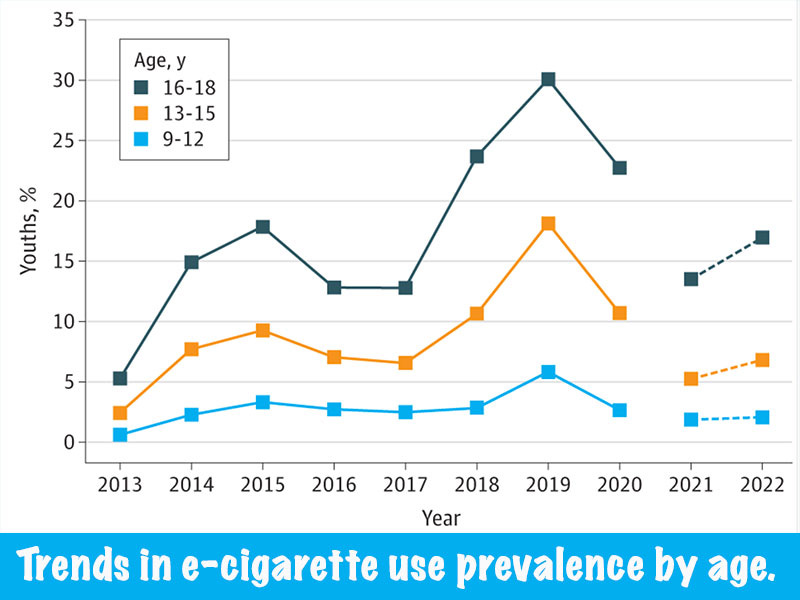

• CHILDREN AND E-CIGARETTES. A study of 186,555 young Americans aged 9–18 from the University of Kentucky, Lexington, and the University of Louisville shows the yo-yo trend of e-cigarette use by age, sex, and race and ethnicity over the last decade. JAMA Network Open

• EXTREME WEATHER. “These go to 11!” One impact of global warming is an expected increase of highly intense cyclones, typhoons, and hurricanes. Should we expand the standard 5-category Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale to account for that? Researchers at MIT say we have already had five “category 6” storms in the last decade. PNAS

• TISSUE ENGINEERING. Reprogramming non-limb “fibroblast” cells into limb progenitor-like cells was successfully done in mice by researchers at Harvard. Developmental Cell

• THE HAPPINESS YOU CAN’T BUY. Global surveys have suggested countrywide wealth and GDP are key predictors of happiness, leading some to assume money is necessary to be happy. But surveying 2,966 people from Indigenous and small local communities in 19 different places, researchers at Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (ICTA-UAB) in Spain found numerous examples of very low-income populations with high average levels of life satisfaction—comparable to wealthy countries. So even if you can’t buy happiness, you can definitely sometimes get it for free. PNAS